6 Costly Data Labeling Mistakes and How To Avoid Them

In data-centric artificial intelligence (data-centric AI), the model is only as good as the data that trains it. And the secret to high-quality training data? High-quality data labeling. Before a model can make any sense of a raw dataset (videos, images, text files, etc.), human annotators must provide the layer of meaning that contextualizes the data.

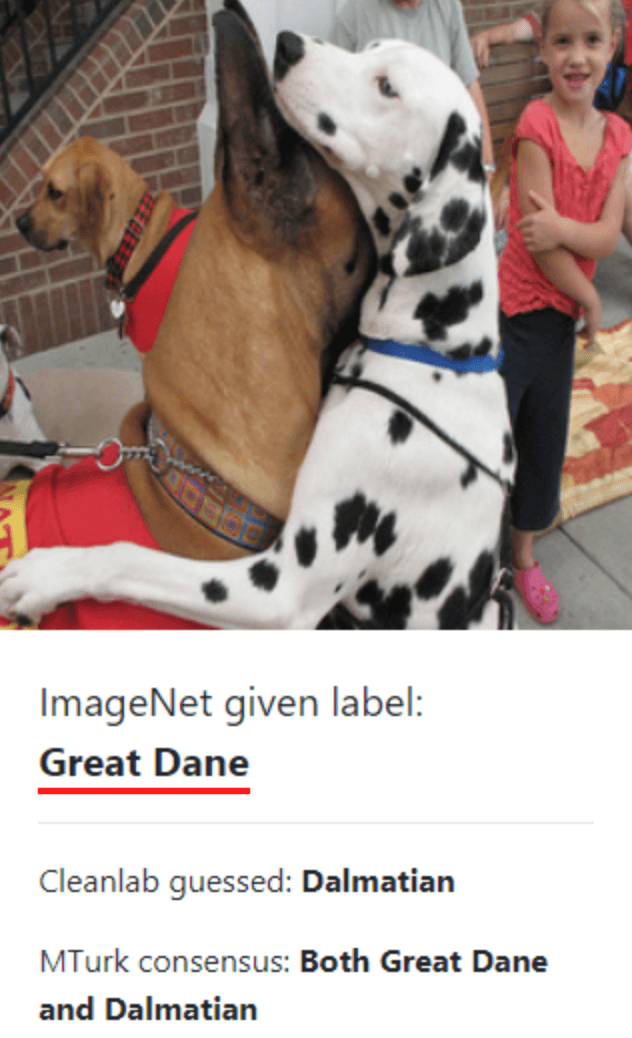

And humans … well, we don’t always get it right. A recent MIT study found that even popular public training datasets like ImageNet have a significant rate of data labeling errors, which it documented on the website Label Errors. When and why do data labeling mistakes like this happen?

It’s not always as simple as blaming the challenges on “human error”—flaws in the data annotation pipeline are often the root causes of mislabeled data. Thankfully, you have control over this factor when you’re managing a machine learning project.

Below are six of the most common and costly data labeling mistakes we see in machine learning projects and the fixes that can help you maintain consistent, accurate training data throughout the project pipeline.

1. Missing Labels

Missing labels can happen with any type of raw data, but they’re especially common during image classification. If the annotator neglects to put a bounding box around every necessary object in an image, they’ve created a missing label error. And while the mistake might sound simple, the implications can be very serious: Consider the self-driving car that can’t recognize every pedestrian.

Let’s take a look at an image pulled from MIT’s Label Errors website. The image was labeled by the ImageNet algorithm, so we don’t actually know which annotation error(s) led to the algorithm’s incorrect prediction, but it can give us a glimpse of why labels get missed.

Image Source: Label Errors

At first glance, it’s hard to tell how many dogs are in the picture. The dalmatian in the foreground is clear, but the Great Dane’s face is obscured. What’s more, there are two additional dogs in the photo; they’re just harder to spot. If you gave this image to an annotator and told them to place a bounding box around every dog, it’s reasonable to assume your annotator might miss one or two dogs if they were fatigued or moving quickly.

The Fix: Use the Consensus Method

The key to catching and mitigating this kind of error is a strong, collaborative data validation process. The consensus method works great: Ask two or more different annotators to label the same sample of images, find the classes where annotators disagree, and revise your instructions until the annotators are able to find consistency. A thorough peer review process can also catch many quality errors.

2. Incorrect Fit

Sometimes the bounding box simply isn’t tight enough around the object. The gaps that are left can add noise to the data, harming the model’s ability to identify the precise object. If every bounding box for a bird contains both the bird and large chunks of blue sky, the algorithm might start to assume the blue sky is a necessary part of being a bird. It would be less likely, then, to correctly identify the object in this image:

Image Source: ResearchGate

Another kind of incorrect fit is the occlusion error. Expectations are a powerful thing, and our brains love to fill in gaps for us. This tendency to “complete the picture” manifests in the occlusion error: when an annotator puts a box around the expected size of the complete object instead of sticking to the visible part.

The Fix: Provide Clear Instructions

You’ll likely find that unclear instructions are at the root of this error. In the instructions you provide for your labelers, clearly define the tolerance/accuracy you’re looking for. Use supporting screengrabs or videos to illustrate what you mean (“good” and “bad” examples are an especially handy way to get the point across).

Useful instructions are a critical part of the labeling process; they help prevent headaches and confusion down the road. Here’s what we need from a set of instructions:

- Clear, specific language

- Guidelines that provide examples, including use cases and edge cases

- Images or videos that reinforce hard-to-follow instructions

- A standardized set of steps or operating procedures to help annotators maintain consistency

- Links to optional or additional resources when necessary for context

A good practice is to have a non-technical friend or colleague give the instructions a once-over. Can they make sense of it at a conceptual level? If not, you might need to fill in some gaps.

3. Midstream Tag Additions

Sometimes annotators don’t discover they need additional entity types until after they’ve started tagging. For example, a customer support chatbot might miss a common customer concern that reveals itself in the labeling process, leading the annotator to add a corresponding tag so they can capture that concern moving forward.

But what about all of the data that was already tagged? Those objects will lack the new tags, leading to inconsistent training data.

The Fix: Lean On Domain Experts Early and Often

The best possible fix is to engage subject matter experts early to help develop the taxonomy and tags. If you, the project manager, aren’t a domain expert, call one in before you build your initial tag list. The domain expert can help guide every part of the project, but their expertise is especially useful during this stage. Have you accounted for every possible label? Are there additional labels you can add? They’ll be able to tell you.

Crowdsourcing can also be really helpful during this stage. If you can think back to the last time you and a group brainstormed a list of ideas, you’ll notice that group lists usually capture more information than any one person can offer. It’s the same idea here: More heads are better than one. Seek input from the other people working on the project, from the engineers to the annotators themselves.

Even with careful planning, it’s often the case that annotators will discover the need for new labels along the way. With Label Studio, administrators can give annotators the ability to add new labels while working on a task to improve accuracy.

4. Overwhelming Tag Lists

Of course, it’s also possible for project managers to arm their annotators with too many initial tags. Sifting through hundreds of tags can overwhelm your annotators, leading to longer, costlier projects.

Guided by fun heuristics like the availability bias, the annotators will then resort to using tags from the beginning of the list instead of scouring the entire list and finding the perfect label every time. This results in training data that doesn’t tell a complete or accurate story about the raw dataset.

Colossal tag lists also force annotators to become increasingly subjective in their choices—which can introduce more room for error. If you’re asked to label a blue square and your tag options are red, yellow, blue, you’ll pick the label “blue.” On the other hand, if you’re served a blue square and your tag options are cerulean, cobalt, navy, aqua, aquamarine, royal blue, midnight blue, you’ll have to start making decisions that might feel, to you, somewhat arbitrary.

The more shades of gray (or blue) you add to a project, the more likely you are to end up with redundant and inconsistent training data.

The Fix: Use Broad Classes With Subtasks

In most cases, it’s a good idea to organize your tags around the broadest possible topics. However, there are certain projects that do require very granular labels. ImageNet famously uses over 100,000 labels—it doesn’t just want its AI to recognize dogs; it wants it to recognize Great Danes, Dalmatians, and Water Spaniels.

If your model calls for a similar level of detail, follow the ImageNet method: Break the annotation task into smaller tasks, with each subtask representing a particular instance of the broader class. This lets annotators search through a more manageable number of broad categories before they get into the weeds.

Label Studio also has the capability to show labels dynamically as a task input, either as a prediction from the model, or from a database lookup. If you have a long list of labeling options, dynamic labeling can save annotators time and also increase the chances of selecting the best label for the object.

5. Annotator Bias

Biased models result from having too many annotators who represent a single, homogeneous point of view. Since that group’s point of view is centered during the annotation process, the algorithm itself starts to center that point of view. This leaves marginalized groups and their interests out of algorithms ranging from search results to recommendations.

There are less insidious forms of annotator bias, too. If you’re working with annotators who speak British English, they’ll call a bag of potato chips “Crisps.” Your American English speakers will label the same data “Chips.” Meanwhile, your British English speakers will reserve the “Chips” label for fries. That inconsistency will reflect in the algorithm itself, which will arbitrarily mix American and British English into its predictions.

Still another form of annotator bias can occur if you bring in annotators with an average base of generalized knowledge and ask them to identify information only a subject matter expert could know. Perhaps you’ve asked an average person to map neurons in the brain when you should really be working with neuroscience students. Or perhaps you’re expecting the average person to know what kind of dog this is:

Image Source: Label Errors

(If you guessed anything other than “Poodle,” you’re a liar).

The Fix: Work With Representative Annotators

To avoid discriminatory algorithms that over- or underrepresent a particular population, hire a diverse group of annotators who reflect the full population impacted by the AI. If that’s not possible, hire a diversity consultant early in your project so they can help guide its direction.

The other types of labeling bias are a matter of domain expertise. If a project calls for specialized knowledge, work with annotators who have that specialized knowledge. It may be tempting to outsource every part of your annotation pipeline, but domain experts are well worth the cost.

That said, outsourcing and crowdsourcing are excellent ways to validate your labels for quality—which can involve catching biases, too. Use outsourcing to supplement your domain experts, not replace them.

6. Siloed Workflows & Legacy Tools

Data has advanced rapidly in scope and complexity since the early days of machine learning. If you’re using in-house or legacy tools and software, your project has almost certainly outgrown the functionality of your software.

A tell-tale sign this is happening? Silos. If your annotators are experiencing communication breakdowns or tasks that slip through the cracks, they’re not working in a collaborative enough software environment.

The Fix: Create a Single Source of Truth With Modern Labeling Software

What you’re looking for here is a single source of truth: a shared project workspace where everyone is working off the same information, updated in real time. In other words, it’s time to update your labeling platform.

Platforms that adapt to meet the unique challenges of modern big data are fully collaborative by design, with shared workspaces, projects, and task management systems. There are defined user roles and access management, allowing you to follow the principle of least privilege and provide the visibility each team member needs. And systems for validating data quality, like metrics that measure annotator consensus and highlight inconsistencies, are baked into the platform.

Looking for labeling software that fits the bill? Heartex’s Label Studio is a user-friendly, fully collaborative labeling platform that integrates with modern data sources. Come give us a try and learn why we’re the most popular open-source labeling platform today.